Hugo Munsterberg

Want To Study Forensic Psychology?

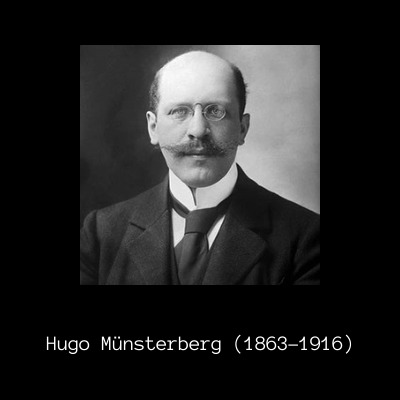

Hugo Munsterberg

Welcome to the Hugo Munsterberg page. The aim of this page is to make the published work of this important and pioneering figure within forensic psychology freely available; beginning with his landmark publication:

ON THE WITNESS STAND: ESSAYS ON PSYCHOLOGY & CRIME (1908)

FOREWORD

The administration of justice is susceptible of division into two general branches: one having to do with the determination of the facts, the other, with the application to the determined facts of legal precepts. The facilities of administration in the jural held have reached a state of high development. In the class-room and the seminar, the attention of the student of law is concentrated upon mastery of legal principles as applied to determined facts; he is educated in legal bibliography and precedent. In practice, legal erudition earns signal commendation and oft-times lucrative reward.

Legal principles have been formulated into rules, doctrines, and statutes, and have been harmonized and codified. The legal practitioner, therefore, usually approaches his task proficient in the knowledge of legal science. But there is the other branch of the administration of justice which is no less important than the jural. It has to do with the domain of facts which holds the dramatic episodes of every controversy between man and man or man and state. For the tasks here the lawyer is not usually well prepared. The ability to discern the facts which control the application of legal principles is not methodically developed. The education and training of a lawyer for eliciting the facts are more or less adventitious.

The difficulties experienced by judges, juries, and lawyers in probing for the truth where conflicting versions are presented are in no small measure responsible for the cynical attitude which is general toward the administration of justice. The effort is often made to overcome contradictory testimony of witnesses, in forensic contest, by crimination and recrimination. Such methods inspire no confidence in the resulting judgment, but produce distrust toward administrative and judicial processes.

Professor Hugo Münsterberg, in this book "On the Witness Stand," in which is collected a series of magazine articles previously published by him, pointed the way to rational and scientific means for probing facts attested by human witnesses, by the application of Experimental Psychology to the administration of law. Psychology had been classified as a pure science. Experimental methods, to the development of which Münsterberg, made notable contribution, have lifted this branch of knowledge into the classification of applied sciences. Applied Psychology can be employed in various fields of practical life - education, medicine, art, economics, and law. Experience has demonstrated that "certain chapters of Applied Psychology" are sources of help and strength for workers in various practical fields, but, says Professor Münsterberg - "The lawyer alone is obdurate. The lawyer and the judge and the juryman are sure that they do not need the experimental psychologist . . .They go on thinking that their legal instinct and their common sense supplies them with all that is needed and somewhat more . . . Just in the line of the law it therefore seems necessary not to rely simply on the technical statements of scholarly treatises, but to carry the discussion in the most popular form possible before the wider tribunal of the general reader."

With that aim in mind the author wrote the popular sketches which are republished in this volume, in which he selected "only a few of the problems in which psychology and law came in contact." Professor Münsterberg was a prolific writer on philosophic and psychological themes. He was a member of a famous group of educators who were associated with Harvard University. In his field, he was a deep scholar and a thorough and intensive researcher. He delighted in the extension of his educational work, and in elucidating the technique of his scientific studies for easy comprehension by lay minds. He had a fascinating style of writing.

In the work which is now republished, Professor Münsterberg furnished an instructive exposition of what may "legal psychology." Although the articles were first published about fourteen years ago, they have lost none of their timeliness, interest, or helpfulness. They introduce the reader to the subject of psychology as a science; and they contain lessons in experimental psychology which are invaluable to any one interested in the administration of justice. The book should stimulate an interest in the study of this branch of knowledge, which should form an important and essential adjunct of the equipment of every investigator and trier of fact, and should encourage the application of this science to practical use in testing the truth or accuracy of historical narrative by witnesses.

CHALRLES S. WHITMAN (Ex-Governor of New York -Former District Attorney of New York County)

INTRODUCTION

There are about fifty psychological laboratories in the United States alone. The average educated man has hitherto not noticed this. If he chances to hear of such places, he fancies that they serve for mental healing, or telepathic mysteries, or spiritistic performances. What else can a laboratory have to do with the mind? Has not the soul been for two thousand years the domain of the philosopher? What has psychology to do with electric batteries and intricate machines? Too often have I read such questions in the faces of visiting friends who came to the Harvard Psychological Laboratory in Emerson Hall and found, with surprise, twenty-seven rooms overspun with electric wires and filled with chronoscopes and kymographs and tachistoscopes and ergographs, and a mechanic busy at his work.

The development of this new science could remain unnoticed because it was such a rapid one, surprising in its extent even to those who started it. When, as a young student, I went to the University of Leipzig in the eighties of the last century, the little psychological laboratory there, founded by Professor Wundt, was still the only one in the world. No Western country college would to-day be satisfied with those poor little rooms in which the master of the craft made his experiments with his few students. But since that time the Leipzig workshop has been steadily growing, and every year has seen the foundation of new institutes by the pupils of Wundt, and later by their pupils. The first German laboratory outside of Leipzig was the one which I founded in Freiburg just twenty years ago. At about the same time Stanley Hall and Cattell brought the work from Leipzig over the ocean. Today there exists hardly a university which has not opened a workshop for this youngest of the natural sciences.

But more brilliant than the external expansion has been the inner growth. If the new science started in poor quarters, it was still more modest at the beginning in its outlook toward the work. Experimental psychology did not even start with experiments of its own; it rather took its problems at first from the neighbouring sciences. There was the physiologist or the physician who made careful experiments on the functions of the eye and the ear and the skin and the muscles, and who got in this way somewhat as by-products interesting experimental results on seeing and hearing and touching and acting; and yet all these by-products evidently had psychological importance. Or there was the physicist who had to make experiments to find out how far our human senses can furnish us an exact knowledge of the outer world; and again his results could not but be of importance for the psychology of perception. Or there was perhaps the astronomer who was bothered with his "personal equation," as he was alarmed to find that it took different astronomers different times to register the passing of a star. The astronomers had, therefore, in the interest of their calculations, to make experiments to find out with what rapidity an impression is noticed and reacted upon. But this again was an experimental result which evidently concerned, first of all, the student of mental life.

In this way all kinds of scientists who cared little for psychology had gathered the most various psychological results with experimental methods, and the psychologists saw that they could not afford to ignore such results of natural science. It would not do to go on claiming, for instance, that thought is quick as lightning when the experiments of the astronomers had proved that even the simplest mental act is a slow process, the time of which can be measured. Experimental ,psychology, therefore, started with an effort to repeat on its own account and from its own point of view those researches which others had performed. But it seemed evident that this kind of work would never yield more than some little facts in the periphery of mental life -- borderland facts between mind and body. No one dreamed of the possibility of carrying such experimental method to the higher problems of inner life which seemed the exclusive region of the philosophising psychologist. But as soon as experimental psychology began to work in its own workshops, it was most natural to carry the new method persistently to new and ever new groups of problems. The tools of experiment were now systematically used for the study of memory and the connection of ideas, then of attention and of imagination, of space perception and time sense; slowly they became directed to the problems of feeling and emotion, of impulse and volition, of imitation and reasoning. Groups of mental functions which yesterday seemed beyond the reach of experimental laboratory methods, to-day appear quite accessible. It may be said that there is now hardly a corner of mental life into which experimental psychology has not thrown its searchlight. It may seem strange that this whole wonderful development should have gone on in complete detachment from the problems of practical life. Considering that perception and memory, feeling and emotion, attention and volition, and so on, are the chief factors of our daily life, entering into every one of our enjoyments and duties, experiences and professions, it seems astonishing that no path led from the seclusion of the psychological workshop to the market-place of the world.

Of course this separation was no disadvantage to psychology. It is never a gain when a science begins too early to look aside to practical needs. The longer a discipline can develop itself under the single influence, the search for pure truth, the more solid will be its foundations. But now experimental psychology has reached a stage at which it seems natural and sound to give attention also to its possible service for the practical needs of life. This must not be misunderstood. To make psychology serviceable cannot mean simply to pick up some bits of theoretical psychology and to throw them down before the public. Just this has sometimes been done by amateurish hands and with disastrous results. Undigested psychological knowledge has been in the past recklessly forced on helpless schoolteachers, and in educational meetings the blackboards were at one time filled with drawings of ganglion cells and tables of reaction-times. No warning against such "yellow psychology" can be serious enough. If experimental psychology is to enter into its period of practical service, it cannot be a question of simply using the ready-made results for ends which were not in view during the experiments. What is needed is to adjust research to the practical problems themselves and thus, for instance, when education is in question, to start psychological experiments directly from educational problems. Applied Psychology will then become an independent experimental science which stands related to the ordinary experimental psychology as engineering to physics.

The time for such Applied Psychology is surely near, and work has been started from most various sides. Those fields of practical life which come first in question may be said to be education, medicine, art, economics, and law. The educator will certainly not resist the suggestion that systematic experiments on memory or attention, for instance, can be useful for his pedagogical efforts. The physician to-day doubts still less that he can be aided in the understanding of nervous and mental diseases, or in the understanding of pain and of mental factors in treatment, by the psychological studies of the laboratory.

It is also not difficult to convince the artist that his instinctive creation may well be supplemented by the psychologist's study of colour and form, of rhythm and harmony, of suggestion and aesthetic emotion. And even the business world begins to understand that the effectiveness of economic life depends in a thousand forms on factors for which the student of psychology is a real specialist. His experiments can indicate best how the energies of mill-hands can reach the best results, and how advertisements ought to be shaped, and what belongs to ideal salesmanship. And experience shows that the politician who wants to know and to master minds, the naturalist who needs to use his mind in the service of discovery, the officer who wants to keep up discipline, and the minister who wants to open minds to inspiration -- all are ready to see that certain chapters of Applied Psychology are sources of help and strength for them. The lawyer alone is obdurate.

The lawyer and the judge and the juryman are sure that they do not need the experimental psychologist. They do not wish to see that in this field preeminently applied experimental psychology has made strong strides, led by Binet, Stern, Lipmann, Jung, Wertheimer, Gross, Sommer, Aschaffenburg, and other scholars. They go on thinking that their legal instinct and their common sense supplies them with all that is needed and somewhat more; and if the time is ever to come when even the jurist is to show some concession to the spirit of modern psychology, public opinion will have to exert some pressure. Just in the line of the law it therefore seems necessary not to rely simply on the technical statements of scholarly treatises, but to carry the discussion in the most popular form possible before the wider tribunal of the general reader.

With this aim in mind -- while working at a treatise on "Applied Psychology," which is to cover the whole ground with technical detail -- I have written the following popular sketches, which select only a few problems in which psychology and law come in contact. They deal essentially with the mind of the witness on the witness stand; only the last, on the prevention of crime, takes another direction. I have not touched so far the psychology of the attorney, of the judge, or of the jury -- problems which lend themselves to very interesting experimental treatment. Even the psychology of the witness is treated in no way exhaustively; my only purpose is to turn the attention of serious men to an absurdly neglected field which demands the full attention of the social community.

ILLUSIONS

There had been an automobile accident. Before the court one of the witnesses, who had sworn to tell "the whole truth, and nothing but the truth," declared that the entire road was dry and dusty; the other swore that it had rained and the road was muddy. The one said that the automobile was running very slowly; the other, that he had never seen an automobile rushing more rapidly. The first swore that there were only two or three people on the village road; the other, that a large number of men, women, and children were passing by. Both witnesses were highly respectable gentlemen, neither of whom had the slightest interest in changing the facts as he remembered them.

I find among my notes another case, where everything depended upon the time which had passed between a whistle signal from the street and the noise of an explosion. It was of the greatest importance for the court to know whether the time was long enough to walk a certain distance for which at least half a minute was needed. Of two unbiased witnesses, one swore that the time was less than ten seconds; the other that it was more than one minute. Again, there was a case where it was essential to find out whether at a certain riot the number of guests in the hall was larger than the forty who had been invited to attend. There were witnesses who insisted that there could not have been more than twenty persons present, and others who were sure that they saw more than ne hundred. In a case of poisoning, some members of the family testified that the beverage had a disagreeable, sour taste, others, that it was tasteless, and others, that it was sweet. In some Bowery wrangle, one witness was quite certain that a rowdy had taken a beer-mug and kept it in his fist while he beat with it the skull of his comrade; while others saw that the two were separated by a long table, and that the assailant used the mug as a missile, throwing it a distance of six or eight feet.

In another trial, one witness noticed at the sea-shore in moonlight a woman with a child, while another witness was not less sure that it was a man with a dog. And only recently passengers in a train which passed a courtyard were sure, and swore, that they had taken in at a glance the distinct picture of a man whipping a child; one swore that he had a clean-shaven face, a hat, and was standing, while another swore that he had a full beard, no hat, and was sitting on a bench. The other day two most reliable expert shorthand writers felt sure that they had heard the utterances which they wrote down, and yet the records differed widely in important points.

There is no need of heaping up such illustrations from actual cases, as everyone who remembers the last half-dozen murder trials of his city knows with what regularity these differences in reports of witnesses occur. We may abstract from all cases which demand technical knowledge; we want to speak here only of direct observations and of impressions which do not need any special acquaintance with the matter. Wherever real professional knowledge is needed, the door is, of course, open to every variety of opinion, and one famous expert may conscientiously contradict the other. No, we speak here only of those impressions for which every layman is prepared and [p. 18] where there can be no difference of opinion. We further abstract entirely from all cases of intentional deception; the witness who lies offers no psychological interest for the student of illusions. And we exclude all questions of mental disease. Thus there remain the unintentional mistakes of the sound mind, -- and the psychologist must ask at once, Are they all of the same order? Is it inasmuch as the contradictory evidence has to be enough to label them simply as illusions memory. To make memory responsible is indeed the routine way. It is generally taken for granted that we all perceive our surroundings uniformly. In case there were only twenty men in the hall, no one could have seen one hundred, In case the road was muddy, no one can have seen in dusty. In case the man was shaved, no one can have seen the beard.

If there is still disagreement, it must have crept in through the trickery of memory. The perception must be correct; its later reproduction may be false. But do we really all perceive the same thing, and does it have the same meaning to us in our immediated absorption of the surrounding world? Is the court sufficiently aware of the great differences between men's perceptions, and does the court take sufficient trouble to examine the capacities and habits with which the witness moves through the world which he believes he observes? Of course some kind of a "'common-sense" consideration has entered, consciously or unconsciously, into hundreds of judicial decisions, inasmuch as the contradictory evidence has to be sifted. The judges have on such occasions more of less boldly philosophised or psychologised on their own account; but to consult the psychological authorities was out of the question. Legal theorists have even proudly boasted of the fact that the judges always found their way without psychological advice, and yet the records of such cases, for instance, in railroad damages, quickly show that the psychological inspirations of the beach are often directly the opposite of demonstrable facts. To be sure, the judge may bolster up the case with preceding decisions, but even if the old decision was justified, is such an amateur psychologist prepared to decide whether the mental situation is really the same in the new case? Such judicial self-help was unavoidable as long as the psychology of earlier times was hazy and vague but all that has changed with the exact character of the new psychology.

The study of these powers no longer lies outside of the realm of science. The progress of experimental psychology makes it an absurd incongruity that the State should devote its fullest energy to the clearing up of all the physical happenings, but should never ask the psychological expert to determine the value of that factor which becomes most influential-the mind of the witness. The demand that the memory of the witness should be tested with the methods of modern psychology has been raised sometimes, but it seems necessary to add that the study of his perceptive judgment will have to find its way into the court-room, too.

Last winter I made, quite by the way, a little experiment with the students of my regular psychology course in Harvard. Several hundred young men, mostly between twenty and twenty-three, took part. It was a test of a very trivial sort. I asked them simply, without any theoretical introduction, at the beginning of an ordinary lecture, to write down careful answers to a number of questions referring to that which they would see or hear. I urged them to do it as conscientiously and carefully as possible, and the hundreds of answers which I received showed clearly that every one had done his best. I shall confine my report to the first hundred papers taken up at random. At first I showed them a large sheet of white cardboard on which fifty little black squares were pasted in irregular order. I exposed it for five seconds, and asked them how many black spots were on the sheet.

The answers varied between twenty-five and two hundred. The answer, over one hundred, was more frequent than that of below fifty. Only three felt unable to give a definite reply. Then I showed a cardboard which contained only twenty such spots. This time the replies ran up to seventy and down to ten. We had here highly trained, careful observers, whose attention was concentrated on the material, and who had full time for quiet scrutiny. Yet in both cases there were some who believed that they saw seven or eight times more points than some others saw; and yet we should be disinclined to believe in the sincerity of two witnesses, of whom one felt sure that he saw two hundred persons in a hall in which the other found only twenty-five.

My next question referred to the perception of time. I asked the students to give the number of seconds which passed between two loud clicks. I separated the two clicks at first by ten seconds, and in a further experiment by three seconds. When the distance was ten, the answers varied between half a second and sixty seconds, a good number judging forty-five seconds as the right time. The one who called it half a second was a Chinese, while all those whose judgments ranged from one second to sixty seconds were average Americans. When the objective time was three seconds, the answers varied between half a second and fifteen seconds. I emphasise that these large fluctuations showed themselves in spite of the fact that the students knew beforehand that they were to estimate the time interval. The variations would probably have been still greater if the question had been put to them after hearing the sound without previous information; and yet a district attorney hopes for a reliable reply when he inquires of a witness, perhaps of a cabman, how much time passed by between a cry and the shooting in the cab.

In my third experiment I wanted to find out how rapidity is estimated. I had on the platform a large clock with a white dial over which one black pointer moved once around in five seconds. The end of the black pointer, which had the form of an arrow, moved over the edge of the dial with a velocity of ten centimeters in one second; that is, in one second the arrow moved through a space of about a finger's length. Now, I made this clock go for a whole minute, and asked the observers to watch carefully the rapidity of the arrow, and to describe, either in figures or by comparisons with moving objects, the speed with which that arrow moved along. Most men preferred comparisons with other objects. The list begins as follows: man walking slowly; accommodation-train; bicycle-rider; funeral cortège in a city street; trotting dog; faster than trot of man; electric car; express train; goldfish in water; fastest automobile speed; very slowly, like a snail; lively spider; and so on. Would it seem possible that university students, trained in observation, could watch a movement [p. 24] constantly through a whole minute, and yet disagree whether it moved as slowly as a snail or as rapidly as an express-train. And yet it is evident that the form of the experiment excluded every possible mistake of memory and excluded every suggestive influence. The observation was made deliberately and without haste. Those who judged in figures showed not less variation. The list begins: one revolution in two seconds; one revolution in forty-five seconds; three inches a second; twelve feet a second; thirty seconds to the hundred yards; seven miles an hour; fifteen miles an hour; forty miles an hour; and so on. In reality the arrow would have moved in an hour about a third of a mile. Not a few of the judgments, therefore, multiplied the speed by more than one hundred.

In my next test I asked the class to describe the sound they would hear and to say from what source it came. The sound which I produced was the tone of a large tuning-fork, which I struck with a little hammer below the desk, invisibly to the students. Among the hundred students whose papers I examined for this record were exactly two who recognised it as a tuning-fork tone. All the other judgments took it for a bell, or an organ-pipe, or a muffled gong, or a brazen instrument, or a horn, or a 'cello string, or a violin, and so on. Or they compared it with as different noises as the growl of a lion, a steam whistle, a fog-horn, a fly-wheel, a human song, and what not. The description, on the other hand, called it: soft, mellow, humming, deep, dull, solemn, resonant, penetrating, full, rumbling, clear, low; but then again, rough, sharp, whistling, and so on. Again I insist that every one knew beforehand that he was to observe the tone, which I announced by a signal. How much more would the judgments have differed if the tone had come in unexpectedly? -- a tone which even now appeared so soft to some and so rough to others -- like a bell to one and like a whistle to his neighbour.I turn to a few experiments in which I showed several sheets of white cardboard, of which each contained a variety of dark and light ink-spots in a somewhat fantastic arrangement. Each of these cards was shown for two seconds, and it was suggested that these rough ink-drawings represented something in the outer world. Immediately after seeing one, the students were to write down what the drawing represented. In some cases the subjects remained sceptical and declared that those spots did not represent anything, but were merely blots of ink. In the larger number the suggestion was effective, and a definite object was recognised.

The list of answers for one picture begins: soldiers in a valley; grapes; a palace; river-bank; Japanese landscape; foliage; rabbit; woodland scene; town with towers; rising storm; shore of lake; garden; flags; men in landscape; hair in curling-papers; china plate; war picture; country square; lake in a jungle; trees with stone wall; clouds; harvest scene; elephant; map; lake with castle in background; trees; and so on. The list of votes for the next picture, which had finer details, started with: spider; landscape; turtle; butterfly; woman's head; bunch of war-flags; ballet-dancers; crowd of people; cactus plant; skunk going down a log; centipede; boat on pond; crow's nest beetle; flower; island; and so forth. There are hardly any repetitions, with the exception that the vague term "landscape" occurs often. Of course, we know, since the days of Hamlet and Polonius, that a cloud can look like a camel and like a whale. And yet such an abundance of variations was hardly to be foreseen.

My next question did not refer to immediate perception, but to a memory image so vividly at every one's disposal that I assumed a right to substitute it directly for a perception. I asked my men to compare the apparent size of the full moon to that of some object held in the hand at arm's length. I explained the question carefully, and said that they were to describe an object just large enough, when seen at arm's length, to cover the whole full moon. My list of answers begins as follows: quarter of a dollar; fair-sized canteloupe; at the horizon, large dinner plate, overhead, dessert-plate; my watch; six inches in diameter; silver dollar; hundred times as large as my watch; man's head; fifty-cent piece; nine inches in diameter; grape-fruit; carriage-wheel; butter-plate; orange; ten feet; two inches; one-cent piece; school-room clock; a pea; soup-plate; fountain-pen; lemon-pie; palm of the hand; three feet in diameter: enough to show, again, the overwhelming manifoldness of the impressions received. To the surprise of my readers, perhaps, it may be added at once that the only man who was right was the one who compared it to a pea. It is most probable that the results would not have been different if I had asked the question on a moonlight night with the full moon overhead. The substitution of the memory image for the immediate perception can hardly have impaired the correctness of the judgments. If in any court the size of a distant object were to be given by witnesses, and one man declared it appeared as large as a pea at arm's distance, and the second as large as a lemon-pie and the third ten feet in diameter, it would hardly be fair to form an objective judgment till the psychologist had found out which mental factors were entering into that estimate.

There were many more experiments in the list; but as I want to avoid all technicality, I refer to only two more, which are somewhat related. First, I showed to the men some pairs of coloured paper squares, and they had ample time to write down which of the two appeared to them darker. At first it was a red and a blue; then a blue and a green; and finally a blue and a grey. My interest was engaged entirely with the last pair. The grey was objectively far lighter than the dark blue, and any one with an unbiased mind who looked at those two squares of paper could have not the slightest doubt that the blue was darker. Yet about one-fifth of the men wrote that the grey was darker.

Now, let us keep this in mind in looking over the last experiment, which I want to report. I stood on the platform behind a low desk and begged the men to watch and to describe everything which I was going to do from one given signal to another. As soon as the signal was given, I lifted with my right hand a little revolving wheel with a colour-disk and made it run and change its color, and all the time, while I kept the little instrument at the height of my head, I turned my eyes eagerly toward it. While this was going on, up to the closing signal, I took with my left hand, at first, a pencil from my vest-pocket and wrote something at the desk; then I took my watch out and laid it on the table; then I took a silver cigarette-box from my pocket, opened it, took a cigarette out of it, closed it with a loud click, and returned it to my pocket; and then came the ending signal. The results showed that eighteen of the hundred had not noticed anything of all that I was doing with my left hand. Pencil and watch and cigarettes had simply not existed for them. The mere fact that I myself seemed to give all my attention to the colour-wheel had evidently inhibited in them the impressions of the other side. Yet I had made my movements of the left arm so ostentatiously, and I had beforehand so earnestly insisted that they ought to watch every single movement, that I hardly expected to make any one overlook the larger part of my actions. It showed that the medium, famous for her slate tricks, was right when she asserted that as soon as she succeeded in turning the attention of her client to the slate in her hand, he would not notice if an elephant should pass behind her through the room.

But the chief interest belongs to the surprising fact that of those eighteen men, fourteen were the same who, in the foregoing experiment, judged the light grey to be darker than the dark blue. That coincidence was, of course, not chance. In the case of the darkness experiment the mere idea of greyness gave to their suggestible minds the belief that the colourless grey must be darker than any colour. They evidently did not judge at all from the optical impression, but entirely from their conception of grey as darkness. The coincidence, therefore, proved clearly how very quickly a little experiment such as this with a piece of blue and grey paper, which can be performed in a few seconds, can pick out for us those minds which are probably unfit to report, whether an action has been performed in their presence or not. Whatever they expect to see they do see; and if the attention is turned in one direction, they are blind and deaf and idiotic in the other.

Enough of my class-room experiments. Might they not indeed work as a warning against the blind confidence in the observations of the average normal man, and might they not reinforce the demand for a more careful study of the individual differences between those on the witness stand? Of course, such study would be one-sided if the psychologist were only to emphasise the varieties of men and the differences by which one man's judgment and observation may be counted on to throw out an opposite report from that of another man. No, the psychologist in the court-room should certainly give not less attention to the analysis of those illusions which are common to all men and of which as yet common sense knows too little. The jurymen and the judge do not discriminate, whether the witness tells that he saw in late twilight a woman in a red gown or one in a blue gown. They are not expected to know that such a faint light would still allow the blue colour sensation to come in, while the red colour sensation would have disappeared.

They are not obliged to know what directions of sound are mixed up by all of us and what are discriminated they do not know, perhaps, that we can never be in doubt whether we heard on the country road a cry from the right or from the left, but we may be utterly unable to say whether we heard it from in front or from behind. They have no reason to know that the victim of a crime; nay have been utterly unable to perceive that he was stabbed with a pointed dagger; he may have felt it like a dull blow. We hear the witnesses talking about the taste of poisoned liquids, and there is probably no one in the jury-box who knows enough of physiological psychology to be aware that the same substance may taste quite differently on different parts of the tongue. We may hear quarrelling parties in a civil suit testify as to the size and length and form of a field as it appeared to them, and yet there is no one to remind the court that the same distance must appear quite differently under a hundred different conditions. The judge listens, perhaps, to a description of things which the witness has secretly seen through the keyhole of the door; he does not understand why all the judgments as to the size of objects and their place are probably erroneous under such circumstances. The witness may be sure of having felt something wet, and yet he may have felt only some smooth, cold metal. In short, every chapter and sub-chapter of sense psychology may help to clear up the chaos and the confusion which prevail in the observation of witnesses.

But, as we have insisted, it is never a question of pure sense perception. Associations, judgments, suggestions, penetrate into every one of our observations. We know from the drawings of [p. 34] children how they believe that they see all that they know really exists; and so do we ourselves believe that we perceive at least all that we expect. I remember some experiments in my laboratory where I showed printed words with an instantaneous illumination. Whenever I spoke a sentence before-hand, I was able to influence the seeing of the word. The printed word was courage: I said something about the university life, and the subject read the word as college. The printed word was Philistines: I, apparently without intention, had said something about colonial policy, and my subject read Philippines. In this way, of course, the fraudulent advertisement makes us overlook some essential element which may change the meaning of the offer entirely. Experimental psychology has at last cleared the ground, and to ignore this whole science and to be satisfied with the primitive psychology of common sense seems really out of order when crime and punishment are in question and the analysis of the mind of the witness might change the whole aspect of the case.

It is enough if we have to suffer from these mental varieties in our daily life; at least the court-room ought to come nearer to the truth, and ought to show the way. The other organs of society may then slowly follow. It may be that, ultimately, even the newspapers may learn then from the legal practice, and may take care that their witnesses be examined, too, as to their capacity of observation. Those experiments described from my class-room recommend at least mildness of judgment when we compare the newspaper reports with each other. Since I saw that my own students do not know whether a point moves with the slowness of a snail or with the rapidity of an express-train; whether a time interval is half a second or a whole minute; whether there are twenty-five points or two hundred; whether a tone comes from a whistle, a gong, or a violin; whether the moon is small as a pea or large as a man, -- I am not surprised any more when I read the reports of the papers.

I had occasion recently to make an address on peace in New York before a large gathering, to which there was an unexpected and somewhat spirited reply. The reporters sat immediately in front of the platform. One man wrote that the audience was so surprised by my speech that it received it in complete silence; another wrote that I was constantly interrupted by loud applause, and that at the end of my address the applause continued for minutes. The one wrote that during my opponent's speech I was constantly smiling; the other noticed that my face remained grave and without a smile. The one said that I grew purple-red from excitement; and the other found that I grew white like chalk. The one told us that my critic, while speaking, walked up and down the large stage; and the other, that he stood all the while at my side and patted me in a fatherly way on the shoulder. And Mr. Dooley finally heard that before I made my speech on peace I was introduced as the Professor from the Harvard War School -- but it may be that Mr. Dooley was not himself present.

THE MEMORY OF THE WITNESS

Last summer I had to face a jury as witness in a trial. While I was with my family at the seashore my city house had been burglarised and I was called upon to give an account of my findings against the culprit whom they had caught with a part of the booty. I reported under oath that the burglars had entered through a cellar window, and then described what rooms they had visited. To prove, in answer to a direct question, that they had been there at night, I told that I had found drops of candle wax on the second floor. To show that they intended to return, I reported that they had left a large mantel clock, packed in wrapping paper, on the dining-room table. Finally, as to the amount of clothes which they had taken, I asserted that the burglars did not get more than a specified list which I had given the police.

Only a few days later I found that every one of these statements was wrong. They had not entered through the window, but had broken the lock of the cellar door; the clock was not packed by them in wrapping paper, but in a tablecloth; the candle droppings were not on the second floor, but in the attic; the list of lost garments was to be increased by seven more pieces; and while my story under oath spoke always of two burglars, I do not know that there was more than one. How did all those mistakes occur? I have no right to excuse myself on the plea of a bad memory. During the last eighteen years I have delivered about three thousand university lectures. For those three thousand coherent addresses I had not once a single written or printed line or any notes whatever on the platform; and yet there has never been a moment when I have had to stop for a name or for the connection of the thought. My memory serves me therefore rather generously. I stood there, also, without prejudice against the defendant. Inasmuch as he expects to spend the next twelve years at a place of residence where he will have little chance to read my writings, I may confess frankly that I liked the man. I was thus under the most favourable conditions for speaking the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and, as there is probably no need for the assurance of my best intentions, I felt myself somewhat alarmed in seeing how many illusions had come in.

Of course, I had not made any careful examination of the house. I had rushed in from the seashore as soon as the police notified me, in the fear that valuable contents of the house might have been destroyed or plundered. When I saw that they had treated me mildly, inasmuch as they had started in the wine cellar and had forgotten under its genial influence, on the whole, what they had come for, I had taken only a superficial survey. That a clock was lying on the table, packed ready to be taken away, had impressed itself clearly on my memory; but that it was packed in a tablecloth had made evidently too slight an impression on my consciousness. My imagination gradually substituted the more usual method of packing with wrapping paper, and I was ready to take an oath on it until I went back later, at the end of the summer vacation. In the same way I got a vivid image of the candle droppings on the floor, but as, at the moment of the perception, no interest was attached to the peculiar place where I saw them, I slowly substituted in my memory the second door for the attic, knowing surely from strewn papers and other disorder that they had ransacked both places. As to the clothes, I had simply forgotten that I had put several suits in a remote wardrobe; only later did I find it empty. My other two blunders clearly arose under the influence of suggestion. The police and every one about the house had always taken as a matter of course that the entrance was made by a cellar window, as it would have been much more difficult to use the locked doors. I had thus never examined the other hypothesis, and yet it was found later that they did succeed in removing the lock of a door. And finally, my whole story under oath referred to two burglars, without any doubt at the moment. The fact is, they had caught the gentleman in question when he, a few days later, plundered another house. He then shot a policeman, but was arrested, and in his room they found a jacket with my name written in it by the tailor. That alone gave a hint that my house also had been entered; but from the first moment he insisted that there had been two in this burglary and that the other [p. 43] man had the remainder of the booty. The other has not been found, and he probably still wears my badges; but I never heard any doubt as to his existence, and thus, in mere imitation, I never doubted that there was a companion, in spite of the fact that every part of the performance might just as well have been carried out by one man alone; and, after all, it is not impossible that he should lie as well as shoot and steal.

In this way, in spite of my best intentions, in spite of good memory and calm mood, a whole series of confusions, of illusions, of forgetting, of wrong conclusions, and of yielding to suggestions were mingled with what I had to report under oath, and my only consolation is the fact that in a thousand courts at a thousand places all over the world, witnesses every day affirm by oath in exactly the same way much worse mixtures of truth and untruth, combinations of memory and of illusion, of knowledge and of suggestion, of experience and wrong conclusions. Not one of my mistakes was of the slightest consequence. But is it probable that this is always so? Is it not more natural to suppose that every day errors creep into the work of justice through wrong evidence which has the outer marks of truth and trust-worthiness? Of course, judge and jury and, later, the newspaper reader try their best to weigh the evidence. Not every sworn statement is accepted as absolute reality. Contradictions between witnesses are too familiar. But the instinctive doubt refers primarily to veracity. The public in the main suspects that the witness lies, while taking for granted that if he is normal and conscious of responsibility he may forget a thing, but it would not believe that he could remember the wrong thing. The confidence in the reliability of memory is so general that the suspicion of memory illusions evidently plays a small role in the mind of the juryman, and even the cross-examining lawyer is mostly dominated by the idea that a false statement is the product of intentional falsehood.

All this is a popular illusion against which modern psychology must seriously protest. Justice would less often miscarry if all who are to weigh evidence were more conscious of the treachery of human memory. Yes, it can be said that, while the court makes the fullest use of all the modern scientific methods when, for instance, a drop of dried blood is to be examined in a murder case, the same court is completely satisfied with the most unscientific and haphazard methods of common prejudice and ignorance when a mental product, especially the memory report of a witness, is to be examined. No juryman would be expected to follow his general impressions in the question as to whether the blood on the murderer's shirt is human or animal. But he is expected to make up his mind as to whether the memory ideas of a witness are objective reproductions of earlier experience or are mixed up with associations and suggestions. The court proceeds as if the physiological chemistry of blood examination had made wonderful progress, while experimental psychology, with its efforts to analyse the mental faculties, still stood where it stood two thousand years ago.

The fact is that experimental psychology has not only in general experienced a wonderful progress during the last decades, but has also given in recent years an unusual amount of attention to just those problems which are involved on the witness stand. It is perhaps no exaggeration to say that a new special science has even grown up' which deals exclusively with the reliability of memory. It started in Germany and has had there for some years even a magazine of its own. But many investigations in France and the United States tended from the start in the same direction, and the work spread rapidly over the psychological laboratories of the world. Rich material has been gathered, and yet practical jurisprudence is, on the whole, still unaware of it; and while the alienist is always a welcome guest in the court room, the psychologist is still a stranger there.

The Court would rather listen for whole days to the "science" of the handwriting experts than allow a witness to be examined with regard to his memory and his power of perception, his attention and his associations, his volition and his suggestibility, with methods which are in accord with the exact work of experimental psychology. It is so much easier everywhere to be satisfied with sharp demarcation lines and to listen only to a yes or no; the man is sane or insane, and if he is sane, he speaks the truth or he lies. The psychologist would upset this satisfaction completely.The administration of an oath is partly responsible for the wrong valuation of the evidence. Its seriousness and solemnity suggest that the conditions for complete truth are given if the witness is ready not to lie.

We are too easily inclined to confuse the idea of truth in a subjective and in an objective sense. A German proverb says, "Children and fools speak the truth," and with it goes the old "In vino veritas." Of course, no one can suppose that children, fools, and tipsy men have a deeper insight into true relations than the sober and grown-up remainder of mankind. What is meant is only that all the motives are lacking which, in our social turmoil, may lead others to the intentional hiding of the truth. Children do not suppress the truth, because they are naïve; the fools do not suppress it, because they are reckless; and the mind under the influence of wine does not suppress it, because the suppressing mechanism of inhibition is temporarily paralysed by alcohol. The subjective truth may thus be secured, and yet the idle talk of the drunkard and the child and the fool may be objectively untrue from beginning to end. It is in this way only that the oath by its religious background and by its connection with threatened punishment can work for truth. It can and will remove to a high degree the intention to hide the truth, but it may be an open question to what degree it can increase the objective truthfulness.

Of course, everyone knows that the oath helps in at least one more direction in curbing misstatements. It not only suppresses the intentional lie, but it focusses the attention on the details of the statement. It excludes the careless, hasty, chance recollection, and stirs the deliberate attention of the witness. He feels the duty of putting his best will into the effort to reproduce the whole truth and nothing but the truth. No psychologist will deny this effect. He will ask only whether the intention alone is sufficient for success and whether the memory is really improved in every respect by increased attention. We are not always sure that our functions run best when we concentrate our effort on them and turn the full light of attention on the details. We may speak fluently, but the moment we begin to give attention to the special movements of our lips and of our tongue in speaking and make a special effort to produce the movements correctly, we are badly hampered. Is it so sure that our memory works faultlessly simply because we earnestly want it to behave well? We may try hard to think of a name and it will not appear in consciousness; and when we have thought of something else for a long time, the desired name suddenly slips into our mind. May it not be in a similar way that the effort for correct recollection under oath may prove powerless to a degree which public opinion underestimates? And no subjective feeling of certainty can be an objective criterion for the desired truth.

A few years ago a painful scene occurred in Berlin, in the University Seminary of Professor von Liszt, the famous criminologist. The Professor had spoken about a book. One of the older students suddenly shouts, "I wanted to throw light on the matter from the standpoint of Christian morality!" Another student throws in, "I cannot stand that!" The first starts up, exclaiming, "You have insulted me!" The second clenches his fist and cries, "If you say another word --" The first draws a revolver. The second rushes madly upon him. The Professor steps between them and, as he grasps the man's arm, the revolver goes off. General uproar. In that moment Professor Liszt secures order and asks a part of the students to write an exact account of all that has happened. The whole had been a comedy, carefully planned and rehearsed by the three actors for the purpose of studying the exactitude of observation and recollection. Those who did not write the report at once were, part of them, asked to write it the next day or a week later; and others had to depose their observations 31under cross-examination.

The whole objective performance was cut up into fourteen little parts which referred partly to actions, partly to words. As mistakes there were counted the omissions, the wrong additions and the alterations. The smallest number of mistakes gave twenty-six per cent. of erroneous statements; the largest was eighty per cent. The reports with reference to the second half of the performance, which was more strongly emotional, gave an average of fifteen per cent. more mistakes than those of the first half. Words were put into the mouths or men who had been silent spectators during the whole short episode; actions were attributed to the chief participants of which not the slightest trace existed; and essential parts of the tragi-comedy were completely eliminated from the memory of a number of witnesses.

This dramatic psychological experiment of six years ago opened up a long series of similar tests in a variety of places, with a steady effort to improve the conditions. The most essential condition remained, of course, always the complete naïveté of the witnesses, as the slightest suspicion on their part would destroy the value of the experiment. It seems desirable even that the writing of the protocol should still be done in a state of belief. There was, for instance, two years ago in Göttingen a meeting of a scientific association, made up of jurists, psychologists, and physicians, all, therefore, men well trained in careful observation. Somewhere in the same street there was that evening a public festivity of the carnival. Suddenly, in the midst of the scholarly meeting, the doors open, a clown in highly coloured costume rushes in in mad excitement, and a negro with a revolver in hand follows him. In the middle of the hall first the one, then the other, shouts wild phrases; then the one falls to the ground, the other jumps on him; then a shot, and suddenly both are out of the room. The whole affair took less than twenty seconds. All were completely taken by surprise, and no one, with the exception of the President, had the slightest idea that every word and action had been rehearsed beforehand, or that photographs had been taken of the scene.

It seemed most natural that the President should beg the members to write down individually an exact report, inasmuch as he felt sure that the matter would come before the courts. Of the forty reports handed in, there was only one whose omissions were calculated as amounting to less than twenty per cent. of the characteristic acts; fourteen had twenty to forty per cent of the facts omitted; twelve omitted forty to fifty per cent., and thirteen still more than fifty per cent. But besides the omissions there were only six among the forty which did not contain positively wrong statements; in twenty-four papers up to ten per cent, of the statements were free inventions, and in ten answers -- hat is, in one-fourth of the papers, -- more than ten per cent of the statements were absolutely false, in spite of the fact that they all came from scientifically trained observers. Only four persons, for instance, among forty noticed that the negro had nothing on his head; the others gave him a derby, or a high hat, and so on. In addition to this, a red suit, a brown one, a striped one, a coffee-coloured jacket, shirt sleeves, and similar costumes were invented for him. He wore in reality white trousers and a black jacket with a large red necktie. The scientific commission which reported the details of the inquiry came to the general statement that the majority of the observers omitted or falsified about half of the processes which occurred completely in their field of vision. As was to be expected, the judgment as to the time duration of the act varied between a few seconds and several minutes.

It is not necessary to tell more of these dramatic experiments, which have recently become the fashion and almost a sport, and which will still have to be continued with a great variety of conditions if the psychological laws involved are really to be cleared up. There are many points, for instance, in which the results seem still contradictory. In some cases it was shown that the mistakes made after a week were hardly more frequent more than those made after a day. Other experiments seemed to indicate that the number of mistakes steadily increases with the length of time which has elapsed. Again, some experiments suggest that the memory of the two sexes is not essentially different, while the majority of the tests seems to speak for very considerable difference. Experiments with school children, especially, seem to show that the girls have a better memory than the boys as far as omissions are concerned; they forget less. But they have a worse memory than the boys as far as correctness is concerned; they unintentionally falsify more.

We may consider here still another point which is more directly connected with our purpose. A well-known psychologist showed three pictures, rich in detail, but well adapted to the interest of children, to a large number of boys and girls. They looked at each picture for fifteen seconds and then wrote a full report of everything they could remember. After that they were asked to underline those parts of their reports of which they felt so absolutely certain that they would be ready to take an oath before court on the underlined words. The young people put forth their best efforts, and yet the results showed that there were almost as many mistakes in the underlined sentences as in the rest. This experiment has been often repeated and the results make clear that this happens in a smaller and yet still surprising degree in the case of adults also. The grown-up students of my laboratory commit this kind of perjury all the time.

Subtler experiments which were carried on in my laboratory for a long time showed that this subjective feeling of certainty can not only obtain in different degrees, but has, with different individuals, quite different mental structure and meaning. We found that there were, above all, two distinct classes. For one of those types certainty in the recollection of an experience would rest very largely upon the vividness of the image. For the other type it would depend upon the congruity of an image with other previously accepted images; that is, on the absence of conflicts, when the experience judged about is imagined as part of a wide setting of past experiences. But the most surprising result of those studies was perhaps that the feeling of certainty stands in no definite relation to the attention with which the objects are observed. If we turn our attention with strongest effort to certain parts of a complex impression, we may yet feel in our recollection more certain about those parts of which we hardly took notice than about those to which we devoted our attention. The correlations between attention, recollection, and feeling of certainty become the more complex the more we carefully study them. Not only the self-made psychology of the average juryman, but also the scanty psychological statements which judge and attorney find in the large compendiums on Evidence fall to pieces if a careful examination approaches the mental facts.

The sources of error begin, of course, before the recollection sets in. The observation itself may be defective and illusory; wrong associations may make it imperfect; judgments may misinterpret the experience; and suggestive influences may falsify the data of the senses. Everyone knows the almost unlimited individual differences in the power of correct observation and judgment. Everyone knows that there are persons who, under favourable conditions, see what they are expected to see. The prestidigitateurs, the fakirs, the spiritualists could not play their tricks if they could not rely on associations and suggestions, and it would not be so difficult to read proofs if we did not usually see the letters which we expect. But we can abstract here from the distortions which enter into the perception itself; we have discussed them before. The mistakes of recollection alone are now the object of our inquiry and we may throw light on them from still another side.

Many of us remember minutes in which we passed through an experience with a distinct and almost uncanny feeling of having passed through it once before. The words which we hear, the actions which we see, we remember exactly that we experienced them a long time ago. The case is rare with men, but with women extremely frequent, and there are few women who do not know the state. An idea is there distinctly coupled with the feeling of remembrance and recognition, and yet it is only an-associated sensation, resulting from fatigue or excitement, and without the slightest objective basis in the past. The psychologist feels no difficulty in explaining it, but it ought to stand as a great warning signal before the minds of those who believe that the feeling of certainty in recollection secures objective truth. There is no new principle involved, of course, when the ideas which stream into consciousness spring from one's own imagination instead of being produced by the outer impressions of our surroundings. Any imaginative thought may slip into our consciousness and may carry with it in the same way that curious feeling that it is merely the repetition of something we have experienced before.

A striking illustration is well known to those who have ever taken the trouble to approach the depressing literature of modern mysticism. There we find an abundance of cases reported which seem to prove that either prophetic fortune tellers or inspired dreams have anticipated the real future of a man's life with the subtlest details and with the most uncanny foresight. But as soon as we examine these wonderful stories, we find that the coincidences are surprising only in those cases in which the dreams and the prophecies have been written down after the realisation. Whenever the visions were given to the protocol before-hand, the percentage of true realisations remains completely within the narrow limits of chance coincidents and natural probability. In other words, there cannot be any doubt that the reports of such prophecies which are communicated after having been realised are falsified. That does not reflect in the least on the subjective veracity; our satisfied client of the clever fortune teller would feel ready to take oath to his illusions of memory; but illusions they remain. He also, in most cases, feels sure that he told the dream to the whole family the next morning exactly as it happened; only when it is possible to call the members of the family to a scientific witness stand, does it become evident that the essentials of the dream varied in all directions from the real later occurrence. The real present occurrence completely transforms the reminiscences of the past prophecy and every happening is apperceived with the illusory overtone of having been foreseen.

We must always keep in mind that a content of consciousness is in itself independent of its relation to the past and has thus in itself no mark which can indicate whether it was experienced once before or not. The feeling of belonging to our past life may associate itself thus just as well with a perfectly new idea of our imagination as with a real reproduction of an earlier state of mind. As a matter of course, the opposite can thus happen, too; that is, an earlier experience may come to our memory stripped of every reference to the past, standing before our mind like a completely new product of imagination. To point again to an apparently mysterious experience: the crystal gazer feels in his half hypnotic state a free play of inspired imagination, and yet in reality he experiences only a stirring up of the deeper layers of memory pictures. They rush to his mind without any reference to their past origin, picturing a timeless truth which is surprisingly correct only because it is the result of a sharpened memory. Yes, we fill the blanks of our perceptions constantly with bits of reproduced memory material and take those reproductions for immediate impressions. In short, we never know from the material itself whether we remember, perceive, or imagine, and in the borderland regions there must result plenty of confusion which cannot always remain without dangerous consequences in the court-room.Still another phenomenon is fairly familiar to everyone, and only the courts have not yet discovered it. There are different types of memory, which in a very crude and superficial classification might be grouped as visual, acoustical, and motor types. There are persons who can reproduce a landscape or a painting in full vivid colours and with sharp outlines throughout the field, while they would be unable to hear internally a melody or the sound of a voice.

There are others with whom every tune can easily resound in recollection and who can hardly read a letter of a friend without hearing his voice in every word, while they are utterly unable to awake an optical image. There are others again whose sensorial reproduction is poor in both respects; they feel intentions of movement, as of speaking, of writing, of acting, whenever they reconstruct past experience. In reality the number of types is much larger. Scores of memory variations can be discriminated. Let your friends describe how they have before their minds yesterday's dinner table and the conversation around it, and there will no be two whose memory shows the same scheme and method. Now we should not ask a short-sighted man for the slight visual details of a far distant scene, yet it cannot be safer to ask a man of the acoustical memory type for strictly optical recollections. No one on the witness stand is to-day examined to ascertain in what directions his memory is probably trustworthy and reliable; he may be asked what he has seen, what he has heard, what he as spoken, how he has acted, and yet even a most superficial test might show that the mechanism of his memory would be excellent for one of these four groups of questions and utterly useless for the others, however solemnly he might keep his oath.

The courts will have to learn, sooner or later, that the individual differences of men can be tested to-day by the methods of experimental psychology far beyond anything which common sense and social experience suggest. Modern law welcomes, for instance, for identification of criminals all the discoveries of anatomists and physiologists as to the individual differences; even the different play of lines in the thumb is carefully registered in wax. But no one asks for the striking differences as to those mental details which the psychological experiments on memory and attention, on feeling and imagination, on perception and discrimination, on judgment and suggestion, on emotion and volition, have brought out in the last decade. Other sciences are less slow to learn. It has been found, for instance, that the psychological speech impulse has for every individual a special character as to intonation and melody. At once the philologists came and made the most brilliant use of this psychological discovery. They have taken, for instance, whole epic texts and examined those lines as to which it was doubtful whether they belonged originally to the poem or were later interpolations. Wherever the speech intonation agreed with that of the whole song, they acknowledged the authentic origin, and where it did not agree they recognised an interpolation of the text. Yet the lawyers might learn endlessly more from the psychologists about individual differences than the philologians have done. They must only understand that the working of the mental mechanism in a personality depends on the constant cooperation of simple and elementary functions which the modern laboratory experiment can isolate and test.

If those simplest elements are understood, their complex combination becomes necessary; just as the whole of a geometrical curve becomes necessary as soon as its analytical formula is understood for the smallest part.But the psychological assistance ought not to be confined to the discrimination of memory types and other individual differences. The experimentalist cannot forget how abundant are the new facts of memory variations which have come out of experiments on attention and inhibition. We know and can test with the subtlest means the waves of fluctuating attention through which ideas become reinforced and weakened. We know, above all, the inhibitory influences which result from excitements and emotions which may completely change the products of an otherwise faithful memory.

A concrete illustration may indicate the method of the experimenters. The judge has to make up his mind as soon as there is any doubt on which side the evidence on an issue of fact preponderates. If it can be presupposed that both sides intend to speak the truth he is ready to consider that the one side had, perhaps, a more frequent opportunity to watch the facts in question, the other side, perhaps, saw them more recently; the one saw them, perhaps, under especially impressive circumstances, the other, perhaps, with further knowledge of the whole situation, and so on. Of course, his buckram-bound volumes of old decisions guide him, but those decisions report again only that the one or the other judge, relying on his common-sense, thought recency more weighty than frequency, or frequency more important than impressiveness, or perhaps the opposite.

It is the same way in which common-sense tells a man what kind of diet is most nourishing. Yet what responsible physician would ignore the painstaking experiments of the physiological laboratory, determining exactly the quantitative results as to the nourishing value of eggs or milk or meat or bread? The judges ignore the fact that with the same accuracy their common-sense can be transformed into careful measurements the results of which may widely differ from haphazard opinion. The psychologist, of course, has to reduce the complex facts to simple principles and elements. An investigation, devoted to this problem of the relative effectiveness of recency, frequency, and vividness was carried on in my psychological laboratory. Here we used simple pairs of coloured papers and printed figures, or colours and words, or words and figures, or colours and forms, and so on. A series of ten such pairs may be exposed successively in a lighted field, each time one colour and one figure of two digits. But one pair, perhaps the third, is repeated as the seventh, and thus impresses itself by its frequency; another pair, perhaps the fifth, comes with impressive vividness, from the fact that instead of two digits, suddenly three are used. The last pair has, of course, the advantage in that it sticks to the mind from its position at the end; it remains the most recent, which is not inhibited by any following pair. After a pause the colours are shown again and every one of the subjects has to write down the figures together with which he believes himself to have seen the particular colours.

Is the vivid pair, or the frequently repeated pair, or the recent pair better remembered? Of course, the experiment was made under most different conditions, with different pauses, different material, different length of the series, different influences, different distribution, different subjects, but after some years of work, facts showed themselves which can stand as facts. The relative value of the various conditions for exact recollection became really measurable. They may and must be corrected by further experiments, but they are raised from the first above the level of the chance opinions of the lawyer-psychologist.

All this remains entirely within the limits of the normal healthy individuality. Nothing of all that we have mentioned belongs to the domain of the physician. Where the alienist has to speak, that is, where pathological amnesia destroys the memory of the witness, or where hallucinations of disease, or fixed ideas deprive the witness's remembrance of their value, there the psychologist is not needed. It is in normal mental life and its border-land regions that the progress ofpsychological science cannot be further ignored. No railroad or ship company would appoint to a responsible post in its service men whose eyesight had not been tested for colour blindness. There may be only one among thirty or forty who cannot distinguish at a distance the red from the green lantern. Yet if he slips into the service without being tested, his slight defect, which does not disturb him in practical life and which he may never have noticed if he was not just picking red strawberries among green leaves, may be sufficient to bring about the most disastrous wrecking of two trains or the most horrible collision of steamers. In the life of justice trains are wrecked and ships are colliding too often, simply because the law does not care to examine the mental colour blindness of the witness's memory. And yet we have not even touched one factor which, more than anything else, devastates memory and plays havoc with our best intended recollections: that is, the power of suggestion.

THE DETECTION OF CRIME

As old as the history of crime is the history of cruelties exercised, in the service of justice, for the discovery of criminal facts. Man has the power to hide his knowledge and his memories by silence and by lies, and the infliction of physical and mental pain has always seemed the quickest way to untie the tongue and to force the confession of truth. Through thousands of years, in every land on the globe, accomplices have been named, crimes have been acknowledged, secrets have been given up, under threats and tortures which overwhelmed the will to resist. The imagination of the Orient invented more dastardly tortures than that of the Occident; the mediaeval Inquisition brought the system to perhaps fuller perfection than later centuries; and to-day the fortresses of Russia are said to witness tortures which would be impossible in non-Slavic lands. And, although the forms have changed, can there be any doubt that even in the United States brutality is still a favourite method of undermining the mental resistance of the accused? There are no longer any thumb-screws, but the lower orders of the police have still uncounted means to make the prisoner's life uncomfortable and perhaps intolerable, and to break down his energy. A rat put secretly into a woman's cell may exhaust her nervous system and her inner strength till she is unable to stick to her story. The dazzling light and the cold-water hose and the secret blow seem still to serve, even if nine-tenths of the newspaper stories of the "third degree" are exaggerated. Worst of all are the brutal shocks given with fiendish cruelty to the terrified imagination of the suspect.

Decent public opinion stands firmly against such barbarism; and this opposition springs not only from sentimental horror and from aesthetic disgust: stronger, perhaps, than either of these is the instinctive conviction that the method is ineffective in bringing out the real truth. At all times, innocent men have been accused by the tortured ones, crimes which were never committed have been confessed, infamous lies have been invented, to satisfy the demands of the torturers. Under pain and fear a man may make any admission which will relieve his suffering, and, still more misleading, his mind may lose the power to discriminate between illusion and real memory. Enlightened juries have begun to understand how the ends of justice are frustrated by such methods. Only recently an American jury, according to the newspapers, acquitted a suspect who, after a previous denial, confessed with full detail to having murdered a girl whose slain body had been found. The detectives had taken the shabby young man to the undertaking-rooms, led him to the side of the coffin, suddenly whipped back the sheet, exposing the white bruised face, and abruptly demanded, "When did you see her?" He sank on his knees and put his hands over his face; but they dragged him to his feet and ordered him to place his right hand on the forehead of the body. Shuddering, he obeyed, and the next moment again collapsed. The detectives pulled him again to his feet, and fired at him question after question, forcing him to stroke the girl's hair and cheeks; and, evidently without control of his mind, he affirmed all that his torturers asked, and, in his half-demented state, even added details to his untrue story.

The clean conscience of a modern nation rejects every such brutal scheme in the search of truth, and yet is painfully aware that the accredited means for unveiling the facts are too often insufficient. The more complex the machinery of our social life, the easier it seems to cover the traces of crime and to hide the outrage by lies and deception. Under these circumstances, it is surprising and seems unjustifiable that lawyers and laymen alike should not have given any attention, so far, to the methods of measurement of association which experimental psychology has developed in recent years. Of course, the same holds true of many other methods of the psychological laboratory -- methods in the study of memory and attention, feeling and will, perception and judgment, suggestion and emotion. In every one of these fields the psychological experiment could be made helpful to the purposes of court and law. But it is the study and measurement of associations which have particular value in those realms where the barbarisms of the third degree were formerly in use. The chronoscope of the modern psychologist has become, and will become more and more, for the student of crime what the microscope is for the student of disease. It makes visible that which remains otherwise invisible, and shows minute facts which allow a clear diagnosis. The physician needs his magnifier to find out whether there are tubercles in the sputum: the legal psychologist may in the future use his mental microscope to make sure whether there are lies in the mind of the suspect.